Earlier today, at about 2 plus in the afternoon, you might have noticed your office lights flickered, the escalators came to a standstill or that the chillers had tripped.

Enough clues to guess what could have been the cause?

Yes, you guessed it right. There was a transmission level fault, hence causing an islandwide voltage dip.

Here, in Singapore. a voltage dip is defined as a drop of more than 10% of the nominal voltage (Line voltage). It typically lasts around 200ms.

In Singapore, the transmission network consists of a 400kV network, overlayed onto 4 x 230kV blocks. The 230kV blocks were split up in the mid 2000s, for controlling of fault level.

It has inherently brought an advantage: Minimize the impact of a voltage dip due to a 230kV transmission fault to just that particular block.

Hence in a 230kV fault, only connected customers in that particular block which the fault occurred will ‘see’ severe dip values (in the ranges of 40-50% dip by magnitude); Customers in the lower voltage levels (66kV, 22kV etc) of that block will see similar (as seen at 230kV) dip severity or less (slightly). The other 3 blocks will see significantly less severe voltage dip or just a slight variation of the nominal voltage.

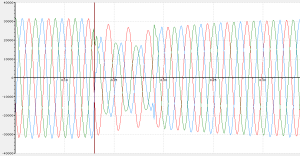

This is what happened earlier. Below is the 22kV (Line to Line) voltage dip snapshot, captured from one of the monitoring sites in the western part of Singapore.

Monitoring sites in other parts of Singapore also registered similar dip patterns, suggesting a transmission level fault.

This brings me to the conclusion that

1) This was a 230kV single phase fault on the L3 (Blue phase) in the western part of Singapore.

UPDATE 31/10: Official Letter from SP PowerAssets: 230kV Cable damage – between Tuas Substation and Jurong Pier Substation at about 2:13 PM, 30/10/2013.

2) An L3 fault occurred. This affected V23 and V31 significantly. Hence you can notice both V23 and V31 ‘dropped’.

Singapore’s 230kv network is solidly grounded; hence any single phase fault will cause the other two non-faulted phases to ‘drop’ slightly too. This is unlike in a resistive earthed grounded system, (thru the Neutral Ground resistor) where the other two non-faulted phases will swell.

Here it also shows the advantages of having a power quality monitoring system installed. With both voltage and current waveforms recorded during a dip, it will assist the experienced engineer in analyzing whether the drop in voltage was caused by a fault downstream (internal fault) or originated from the grid (external fault); and hence assist him in quicken the restoration time for equipment that could have tripped due to the voltage dip.